- Homepage

- Brand

- Antique (19)

- Capodimonte (22)

- Coalport (40)

- Continental (21)

- Department 56 (15)

- Dresden (40)

- Dresden Porcelain (18)

- Herend (292)

- Kpm (18)

- Limoges (68)

- Meissen (68)

- Nippon (48)

- Ralph Lauren (12)

- Rosenthal (14)

- Royal Doulton (21)

- Royal Vienna (27)

- Royal Worcester (56)

- Trio (13)

- Unmarked (46)

- Zsolnay (16)

- ... (3945)

- Chinese Dynasty

- 1950-1999 (2)

- 20th Century (5)

- Kangxi (7)

- Kangxi(1662-1722) (3)

- Ming (1368-1644) (37)

- Qianlong (13)

- Qing (1644-1911) (564)

- Republic (5)

- Republic / Proc (2)

- Republic Of China (6)

- Republic Period (3)

- Song (2)

- Song (960-1279) (3)

- Tang (618-907) (2)

- Transitional (3)

- Unknown (2)

- Yongzheng (2)

- 清朝 (2)

- ... (4156)

- Features

- 8 Day Movement (5)

- Adjustable (6)

- Antique (5)

- Artist Made (4)

- Blue And White (2)

- Boxed (10)

- Date-lined (16)

- Decorated (2)

- Decorative (32)

- Framed (7)

- Hand Painted (633)

- Handcarved (55)

- Handmade (3)

- Handpainted (832)

- Handpainted, Signed (92)

- Lamp Shade Included (3)

- Realistic / Lifelike (10)

- Retired (2)

- Signed (9)

- Signed, Handpainted (2)

- ... (3089)

- Material

- Bone China (7)

- Brass (6)

- Brass, Porcelain (3)

- Bronze (2)

- Ceramic (17)

- Ceramic & Porcelain (33)

- Ceramic / Porcelain (25)

- Ceramic / Pottery (4)

- Ceramic, Porcelain (40)

- China / Porcelain (16)

- Glass (3)

- Metal (8)

- Ormolu (2)

- Porcelain (1136)

- Porcelain / China (125)

- Porcelain, Cut Steel (3)

- Porzellan (4)

- ... (3385)

- Product

- Type

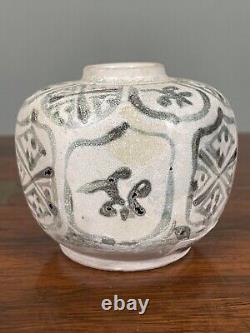

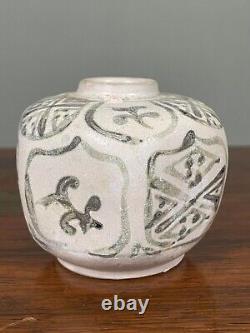

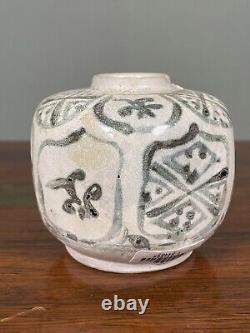

Hoi An Hoard Chinese Shipwreck Hexagonal Jarlet c1480

Hoi An Hoard Chinese Shipwreck Hexagonal Jarlet c1480. This hexagonal jarlet has been freely hand painted with bold panels of shapes and scrolls. Condition: Marine shell/residue at the neck rim, an overall dulling of the glaze in appearance.

Size: Height: 6cm Diameter: 7cm Provenance: This jarlet retains its original Saga Hoi An Hoard Visal sticker along with lot number 84489 meaning that it can be checked against the Hoi An sale catalogue. If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact.

The Thai vessel, carrying the cargo, sank in the 15. Century near the port of Hoi An. In the early 1990s, fishermen trawling for squid and red snapper stumbled upon the wreck. The find was termed the "Hoi An Hoard".

The Hoi An shipwreck is a very important record of Vietnamese types of Blue and white /enamelled wares found during the 2nd half of 15th century. It displayed a richness of form and decoration previously unknown to ceramics experts on Vietnamese wares.The cargo included dishes, pouring vessels, bottles, jars, cups, bowls, figural ceramics, and cover boxes. During the 15th century, off the Hoi An coast of Vietnam in the South China Sea, the trading vessel filled with porcelain vanished without a trace.

Five hundred years later, in 1999, a storm swept toward this very same area, the archaeological excavation barge Tropical 388 was confronted by the possibility of a similar fate. The divers working out of Tropical 388 were attempting to retrieve artefacts from the wreckage of the trading vessel, the procedure that was hazardous under the best of conditions. By no means were these good conditions. The shipwreck was located in the middle of a typhoon zone known as the Dragon Sea. Down below, the divers battled to return to their diving bell.

The bell was bouncing up to six feet off the seabed, The divers go in and out through the bottom of the bell, so you can imagine how much trouble they were having at this time. It took six hours for the divers and their underwater connections to be locked into the pressurized live-in chamber on board Tropical 388. Even then they were still at the mercy of circumstances beyond their control. The transition from the chamber to a normal surface environment required a three-day depressurization process. Despite the churning meter-and-a-half waves, the divers could not leave their cabin. To emerge without undergoing the proper procedures would mean instant death. This may have been an expedition constructed on a teetering foundation of risks, but trepidation was not allowed to factor into the operation's progress. The team's willingness to participate at all costs signalled their belief in the significance of this particular treasure hunt -- the possibility that a few bits of ceramic found drifting in the sea would result in one of the greatest underwater archaeological discoveries of all time.